Looking through my files of personal reports of unintentional discharges – that’s when someone shoots a gun unexpectedly, whatever the circumstances – it seems about half of those mistakes happen when someone presses the trigger on purpose.

The battle cry that goes with the loud noise that follows is, “But I thought the gun was unloaded!”

One such incident happened to a friend of mine some time ago. She borrowed a PPK/S because she was thinking about getting one of her own, and asked permission from the owner to dryfire the gun so she could feel out the trigger. The owner agreed, so the shooter picked up the gun knowing that it was loaded, and correctly dropped the magazine to begin unloading the gun. She racked the slide, then pointed the gun at the cinderblock wall she had chosen as the safest direction in her immediate environment.[ref] Most walls of modern construction do not stop bullets, but brick and cement walls do – just be aware of ricochet potentials. Try this: put a stack of books or other materials in front of the bare wall, something that can slow the round before it hits the wall and prevent bounceback.[/ref] Then she pressed the trigger.

BANG!

She had just won the Bullet Surprise, finding a round (the hard way) inside a gun after she’d racked the slide.

In many similar incidents, the problem is shooters doing things out of sequence – racking the slide before removing the magazine, for example. But this shooter had done everything in the right order, and still the gun fired unexpectedly. Thank goodness she consciously followed the Other Three Rules, and didn’t just rely on “It’s unloaded…” to keep herself and her family safe. The bullet came to rest in front of the cement wall she had chosen as her backstop. Apart from the shooter’s ringing ears, no permanent harm was done.

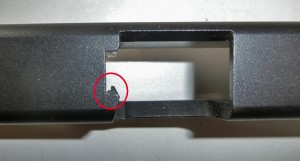

Looking down through the ejection port on a disassembled Glock 26, you can see the extractor — a small bar or hook in front of the breech face near the firing pin.

“I thought the round fell down the mag well and onto the floor when I racked the slide,” my friend told me, “but I was wrong.” Even though she had removed the magazine before she racked the slide, the live round had stayed inside the chamber, ready to fire as soon as the trigger was pressed.

That brings us to an important question:

How could this happen?

This type of mishap can happen for any of several reasons. Sometimes, it’s shooter error: the shooter failed to rack the slide all the way back, and did not move the slide far enough to eject the round. But mechanical mishaps happen too, and they’re far more common.

With a very dirty gun, the gunk and grime from previous rounds may leave a residue that narrows the chamber walls. In those events, the snug case fit keeps the extractor from working as well as it should. Hidden rounds can also happen when the gun’s extractor becomes dirty, worn, or completely broken, or when the ejector fails to do its job for any of the same reasons.

In order to understand how it’s possible to rack the slide but not get the round of the chamber, let’s take a look at how the gun works. The pictures come from a Glock 26, but nearly all semiautos remove chambered rounds using the same basic system that works in the same basic way. Look for these parts on your own gun.

Extractor

You’ll find the extractor near the breech face and firing pin. It’s essentially a small hook or bar that looks a bit like a C clamp. If you look closely, you’ll see that it’s actually a moving part, driven by a tiny but powerful spring. It’s designed to hold the case firmly against the breech face and help pull the case from the chamber when the shooting’s done. As the slide begins to move to the rear, the case will move with the slide because the extractor remains hooked around its rim.

Extracting a live round works almost the same as extracting an empty shell. In both situations, the extractor remains hooked around the case rim as the slide moves to the rear. The only difference is what gets the slide moving. When the gun fires, pressure from the expanding gases pushes both case and slide to the rear, and the extractor simply stays hooked around the empty case as everything moves back together. But when it’s time to remove a live round without firing, the shooter must move the slide herself, by hand. This means the extractor will pull the case from the chamber.[ref] This also means that you can easily miss problems with the extractor while you’re shooting, and will notice them most often when you’re unloading the gun by hand.[/ref]

If the chamber is very dirty, you may have trouble moving the slide when the extractor is hooked around a case rim. That’s because the junk in the chamber won’t let go of the case, and neither will your extractor. While they play tug of war with the case, you’re left struggling with a slide that just won’t move. But sometimes – especially if the extractor has a worn-out spring – instead of stubbornly playing tug of war with the stuck case, the extractor will give up and let go, leaving the case behind in the chamber once you finally get the slide moving.

Something similar can happen if there’s a lot of junk in and around the extractor. Any misplaced debris in that area can jam the extractor open so it cannot grip the case rim when the gun is loaded. Without a good hold on the case rim, the extractor cannot pull the case out of the chamber when you rack the slide.

A worn-out extractor may have a weak spring, or its edges may erode and allow the hook shape to wear away or break off. When any of these things happen, the case rim easily slips out of the extractor’s hold and – again – the case stays behind in the chamber as the slide moves.

Ejector

Ejectors come in different shapes and sizes, but almost all work the same way: they bump the case out of the extractor so it can fly out the ejection port.

As the slide moves to the rear with the extractor holding onto the case, eventually it comes back far enough to approach the ejector. The ejector bumps the side of the case, which pops the case rim out of the extractor. The force of this action makes the unwanted case fly out of the gun’s ejection port.

There are two possible results of a worn or broken ejector.

Most commonly, a broken ejector will cause stovepipe malfunctions while you’re shooting. Stovepipes happen when the unwanted case does not leave the gun, even though the extractor has pulled the case out of the chamber. The old case gets moved aside and gently popped out of the extractor by the new round coming in. But even though the new round will move the old one out of its way, it often won’t have enough force to throw that old case completely out of the gun.[ref] Although sometimes it will. If your gun seems to be working okay, but doesn’t throw brass very far and sometimes leaves an empty case in the chamber on the very last round – which is when there’s no new round coming in to bump the old case out of the extractor’s hold – take a look at your ejector. It may have a broken tip.[/ref] The old case stays in the gun and blocks the port. That also stops the slide from closing, which means you must tap, rack if you want to keep shooting.

The more dangerous result of a broken ejector happens when you unload the gun by hand. In order to unload the gun safely, you always drop the magazine before moving the slide. This is the correct order to unload a gun, of course! But if the gun has a broken ejector, removing the magazine also makes it possible for the extractor to hold onto the unwanted case during the entire motion of the slide – back and forward again. The extractor will pull the round out of the chamber, just as one would expect. But without a working ejector and without a fresh round to feed, there’s nothing left to pop the round out of the extractor’s hold. The extractor remains hooked around the case rim and the round will go straight back into the chamber when the slide goes forward.

Best practice

Now that we know some of the ways the gun can break (or just not work the way we expect it to), it’s a lot easier to understand why simply dropping the magazine and racking the slide should never cause you to trust that the gun is unloaded. And it’s a lot easier to understand why good, experienced shooters want people around them to follow all of the Four Rules, even when “the gun is unloaded.”

When you unload the gun, it’s important to really look at both the chamber and the magazine well. Never just pull the slide back and glance. Lock it open and look.

After you have looked into the gun with the action locked open, double check by feel. Poke your pinky finger into the magazine well to be sure there’s no magazine hiding there. (You’d be surprised how often there is, when people have just glanced at the gun or were thinking about other things when they looked.) Then run your little finger into the chamber to be sure it’s an empty hole and not a hidden round.

Check by sight. Check by feel. Do these simple things by habit every time you unload a gun, and you’ll never win the Bullet Surprise.