Yesterday, I told an untruth. It wasn’t deliberate, but it was an untruth. Here it is: “Doing things that are hard and even unpleasant is the only way we improve as humans.”

The mistake was using the word and. Should have used or instead, for clarity’s sake.[ref]Some people took issue with the word only, but I’ll stand by that one even though any editor will say that sentences with always in them are always wrong, that only is the only word we should not use, and that an unqualified never is never correct. Phooey![/ref] That’s because hard things aren’t necessarily unpleasant things. Sometimes they are, sometimes they’re not; and that was the sense I meant to convey by using the word even. Doing hard things is a given. Finding them unpleasant is often a choice.

But there’s more.

Doing hard things is not pleasant in the same sense that lying in a shaded hammock on a summer day is pleasant, but we can still feel a very strong sense of joy in doing them or in having done them. Hence the popularity of near-cultish, abusively exhausting exercise programs. The high that follows such hard work feels very enjoyable, and worth the effort it takes to get there. More than that, the effort itself, even before the successful conclusion of the work, can feel amazingly pleasant to those who have the right mindset.

Try mowing a full acre of lawn on a hot summer day with a push mower. It’s hard work and you sweat and you itch and the sun beats down on you and maybe you’d rather be lounging on the deck with a cold glass of your favorite beverage. It’s easy to quit, because there are other ways to get the reward of having a good-looking lawn. You might hire a neighbor’s kid, for example. But as you strain with the effort of pushing the mower around the yard in the hot sunshine for hours on end, you might find a fierce joy in it, and find the pleasure of doing it yourself just as rewarding as your final goal of having a manicured lawn.

In fact, the harder the work, the more pleasurable it can be in that sense. If you’ve been cooped up all winter and spring with a painful joint injury, being able to do such work brings a joy all on its own. That’s a particular flavor of joy that can never be felt by someone who hasn’t faced a similar injury. For the rest of us, even if muscles and joints ache with effort, being able to move them effortfully can be a pleasure of its own. That’s the root of the old saying: “Hard work is its own reward.”

Another little side trip here, the point of my message yesterday: sometimes, we might not feel like getting out of the lounge chair and firing up the old lawnmower, but the work still needs to be done, one way or another. We grow as humans when we force ourselves to do the work that needs to be done, when it needs to be done. Joy often comes while putting in the effort, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t an effort. And that’s a type of joy that can only be felt by someone who got out of the shade and went to work.

There’s something else here, something big that I’ve been struggling to articulate for awhile now. Will take a longer stab at this sometime soon, but meanwhile: it’s easy to gain a little bit of skill at most things without any real struggle, without pushing your own limits, without any discomfort at all. But as far as I can tell, it’s impossible to get truly good at something without doing the hard things – which is sometimes unpleasant and always takes you outside your existing comfort zones. That’s why I said that we improve as humans only by doing the hard things. We can take a few baby steps down any given pathway without much effort, but the road always turns uphill at some point. To refuse the uphill climb is to refuse to grow in that area.

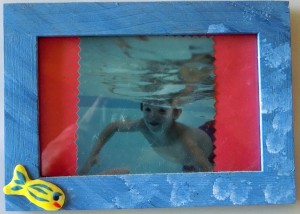

Think of the adorable little guys splashing around in the kiddie pool. They are having fun. Many of them are hollering to their moms: “Mommy! Mommy! Look at me! Watch me swim!!!” They demonstrate their swimming prowess by lying on their tummies in three inches of water, splashing all fours as their bellies and knees hold them above the waterline.

Can those kidlets really swim? Or do they just think they can?

Can they ever become more skilled at staying above water, unless they first let go of the bottom of the pool?

Can anyone become a good swimmer without getting out of the kiddie pool?

One Response to For the joy of it