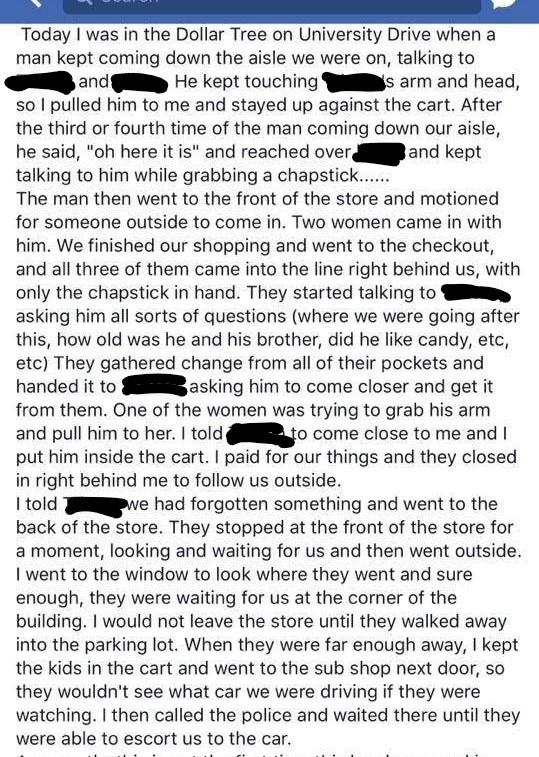

Today I’m thinking about an important question that I found in a private group on Facebook. Shared with permission and with names obscured, here’s the backstory:

To answer the first question you’re most likely to ask after reading the above: Yes, this incident really did happen. Not an urban legend, but something that does sometimes happen to moms with small children. Strangers in the grocery store, apparently stalking them or at least following them around the store, giving off a scary vibe and talking to the children or even touching them.

What’s a responsible concealed-carry person to do in a situation like this? Is this, as an online friend of mine asked, an appropriate time to tell others that we carry a gun? If it’s not, what should we do about persistent strangers who seem to be violating social scripts — who step inside our personal spaces, who talk to or touch our children without permission, who seem to be following us through the store, or who break the social expectations in other ways?

To answer the easiest question first, No. This is not the time to talk about your armed status. Or to pull out the gun. Not yet. In the beginning, this is an ambiguous situation, not a clear-cut one. And the use of a deadly weapon is reserved for times when human lives are definitely in immediate, otherwise unavoidable danger. This isn’t (yet) that. And we don’t know that it ever will be.

We need to find out. And we need to help avoid the situation ending up at that point, if that’s possible.

So … where do we start? Perhaps with this.

The process of self-defense starts long before using the firearm is appropriate, and it includes looking people in the eye and speaking with confidence about what we see.

I think the thing a lot of people miss is that by speaking up and setting a vocal boundary with confidence early on, even when it might feel uncomfortable, we can almost always avoid needing to make a scene — or worse — later on.

Speaking up early does something else: it tells us very clearly who is simply socially clueless, compared to who is actually a real threat to us or our children. I don’t think any of us wants to be the paranoid nutcase who threatens to shoot some nice old lady for looking at our kids funny. The way to avoid disproportionate responses and the way to sort the angels from the demons in this world, is to talk to people.

Examples of how to do that? Sure!

One mom suggests making good eye contact with the stranger, along with a firm, “Please don’t touch my children. You’re too close and it’s making me uncomfortable.”

That’s a great place to start.

To refine this idea, I might tweak the wording a little, and I’d quite willing to use only the first sentence: “Please do not touch my child.” No explanation necessary.

But if I felt as though I had to explain (research does show that strangers more often comply with requests when given a reason), I’d put the explanation before the command, like this:

“You are too close to my child. Please, step back.”

or

“You are too close. Please do not touch my child.”

The situation might be a little different than that, so here are some more possible scripts that a person could tweak as needed to fit the situation:

“We are teaching our child not to talk to strangers. Please do not talk to him.”

“No, she cannot have any candy. Please leave my child alone.”

“You seem to be following us through the store. Please stop.”

Start with a firm and pleasant voice, complete with eye contact. Keep your face neutral. Avoid using a grimmacing “I don’t mean this” smile. No scowl. Polite and neutral is the goal here.

Clearly stating a command — even one phrased as a polite request — to another adult will probably feel really rude the first time you try it, so I suggest role-playing the situation with a spouse or trusted friend until you get the hang of it.

Faced with this type of firm, no-nonsense request, nearly all good people will immediately stop, take a step back, and apologize: “Oh, sorry.” They might follow up with something like, “I was just thinking about my own grandchildren at that age, didn’t mean to make you nervous” — but as they say this, they will be moving away from you and that will be the end of it.

Not-so-good people will persist. They will push. They will try to make you feel guilty for setting boundaries and protecting your children.

This tells you everything you need to know about what is going on.

If the other person responds to your reasonably polite request by…

- calling you a bitch or worse;

- stepping closer to “explain”;

- saying, “Aw, why do you have to be like that?” in a friendly voice while moving closer;

- jerking on your social conscience by asking what you have against (their physical attributes, their religion or race or sexuality or social class or whatever);

- pretending they haven’t heard you and continuing to do whatever-it-was;

- sarcastically saying “geezzzz lady, sooooorrrrrry!”;

- or anything similar to the above

… then you know they do not have your best interest in mind. At this point, armed with this knowledge, you can make a scene. A loud one. Repeat the command, louder and more forcefully. “I said, DO NOT TOUCH MY CHILD.”

If they double down on any of the above, you can quickly move away from them while calling for the store manager at the top of your lungs with a clear conscience. You’ve just learned everything you needed to know about them and their motives for getting close to your child. You can call 9-1-1 while moving away. You can do whatever it takes to call attention to the situation, to put them in the spotlight, to get other people’s eyeballs and attention focused on what is happening.

Do it.

The basic pattern for boundary setting and enforcement is this —

- State boundary (“Please do not touch my child.”)

- Repeat boundary, louder. (“I said, DO NOT TOUCH MY CHILD.”)

- State penalty. (“If you come anywhere near my child again, I will call the police.”)

- Apply penalty.

We’re always tempted to not exactly state our boundaries out loud, just kind of imply them by our actions and trust others to pick up on our facial reactions and body language. That’s the motive behind a lot of not-necessarily-bad ideas that too often fail to solve problems like this — such as telling your child to stay closer to you & not talk to the stranger, or putting the cart between your child and the other person, or heading toward the back of the store, or whatever. All of these are generally also good things to do for various reasons.

But when we do them without clear, out-loud boundary setting, they also send a signal to a true would-be predator that we’re not confident and that we’re not willing to do whatever it takes to protect ourselves and our children.

As far as stating the penalty, that’s important in part because we ourselves must know in our own minds exactly what we will do if the other person does not comply. And we have to have made that decision before we say anything to the other person.

That’s one reason it’s smart to think about and then to explore what we can (legally, socially, ethically) do in response to someone violating social rules and approaching our children — before it ever happens. Where are the limits of our responses? What are each of us willing to do, or not willing to do, in an ambiguous situation? Knowing our limits and what we are willing to do makes it much easier to respond with an appropriate level of confidence in the moment.

If we’re not really brave enough to use our voices to violate the social rule that says, “Don’t bluntly tell other adults what to do,” why would the would-be attacker believe that we would muster the social and physical courage we need to effectively resist an attack?