Spent the weekend playing in the new iteration of the Level 4 Handgun class at the Firearms Academy of Seattle. Orignally signed up to shoot in the class as a student, but had an issue that kept me from shooting (rats!) so instead I enjoyed watching and participating from behind the line. As I watched, I found many learning points to think about.

First things first: Level 4 Handgun is an advanced class that combines elements of pure shooting, gunhandling, and practical skills alongside decision-making and role playing exercises. It’s a hybrid class that takes students through three solid days of hard work, and it’s also a boatload of fun.

Days 1 and 2 of the class comprise the bulk of the shooting instruction and skills refinement, while students enjoy role plays and scenario exercises on Day 3. The third day of the class also offers students an opportunity to pass the very tough Handgun Master Test, a skills assessment that has been part of FAS in various forms since the early 1990s. FAS director Marty Hayes considers that this test provides a brief but reasonably complete overview of a student’s skill with the pistol, and says it is analogous to passing a black belt test in other martial arts. He’s quick to point out that the test is “somewhat arbitrary” in its details, and that there are many other valid ways to test one’s skill with the defensive handgun. The test checks students’ draw speed, accuracy, one-handed skills, reloads, multiple target transitions, low light skills, and ability to hit moving targets. Distances range from 4 yards (for one-hand skills) out to 15 yards (for accuracy), with a majority of the work taking place at car length distances.

The class isn’t about the test, though. The test is simply one component of a well-rounded package of shooting and gunhandling skills. These skills, when mastered, form the backbone of being prepared to think about other things while using the gun quickly and effectively.

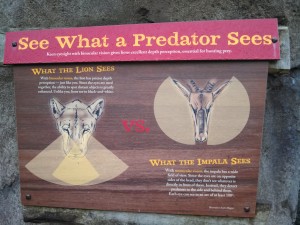

It’s the “thinking about other things” that matters, you see. For people interested in self-defense, that’s where all shooting instruction and practice in smooth gunhandling is supposed to lead: being able to solve the problem without worrying about whether you’d be able to physically do the skill that solving the problem might require. Being able to solve it without consciously thinking about the tool itself or how to use it, because your mind needs to focus on other things.

Instead of using up all our brain cells in remembering how to draw the gun efficiently, hold it safely, see the sights appropriately and manipulate the trigger effectively, we could be using those same brain cells to think about the appropriateness of using the gun to solve the problem:

- Is there another way to solve this problem that does not involve gunfire? If so, what is it and how can I implement it?

- Do I have to shoot? Do I have to shoot right now?

We could be thinking about the people around us:

- Where are my loved ones? Are they out of the line of fire?

- Can I or should I move in order to change the angles and reduce the risk to other innocents? If so, which direction should I move?

- Does the attacker have an accomplice? If so, where?

We could be thinking about the surroundings:

- Where is a position of advantage that I could move to? Do I have time to create distance or get behind cover? Can I do so without increasing my exposure and risk?

- Is there somewhere a second attacker could be hiding? What can I do to reduce my risk from that direction?

New and untrained shooters often must use every bit of spare brain power just to remember how to hold the gun without getting a thumb awkwardly behind the slide, or how to get the gun out of the holster without fumbling and dropping it, or how to be sure that the gun is ready to fire with external safeties in the appropriate position. Even those who are well-practiced in calm conditions on the range may find themselves suddenly needing to think their way through these actions when they’re in a hurry and under stress.

Fortunately, students who have invested in themselves and in their families’ safety by attending professional training classes such as the FAS program will have much more leeway in tough situations. They’re better prepared to make good decisions and shoot effectively, because they’ve engrained both their shooting and their gunhandling skills to the point of automaticity.

Just as a beginning driver might find herself thinking about nothing else other than the mechanics of driving the car, a beginning shooter often has little attention to spare for tasks other than simply running the gun. This can be a problem for both when a crisis looms.

Lots more to say about this excellent class, but this post is already too long. More tomorrow!