If you’ve been following this blog very long, you know that I have literally never featured a guest post before. However, when Glenn Bellamy sent this to my email box the other day, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to shed a little light on an important issue that’s been confusing for a lot of people.

For those who wonder why Cornered Cat would ever talk about political issues related to guns, please [click here.] That should explain things (the short version is, I’m all about teaching women how to protect themselves using guns, and sometimes that means that we need to learn something about how to protect the guns we use to protect ourselves). And if, after reading this excellent article from Glenn Bellamy, you feel motivated to write to your representatives — please do!

What’s the Story Behind ATF “Banning” 5.56mm Ammo?

(. . . and what can you do about it?)

By Glenn D. Bellamy, Armorer-at-Law®

March 5, 2015

There’s been no shortage of misinformation and hyperbole about an ATF memo released on February 13th reported to “ban AR15 ammo.” The memo describes a “framework” by which ATF proposes it would consider requests for “sporting purpose” exemptions under the federal statute banning the manufacture, importation or sale (but not possession) of “armor piercing” projectiles. I’ve searched and research the law and the facts behind it with passion over the last two weeks. I’m tempted to write a legal brief in opposition, or at least to give it a thorough fisking. But that would bore you and be wasted on the ATF at this point.

Instead, I’ll give you the skinny on what’s going on and the most effective thing(s) you can do about it.

The Skinny

Back in 1986, Congress debated — and passed — a law purported to protect law enforcement officers from evil “cop killer” bullets (the Law Enforcement Officers Protection Act). Since virtually every rifle round will penetrate the soft body armor worn by police, the law became focused on ammunition designed for handguns. Rather than define what would be prohibited by performance (whether it could penetrate body armor), they compromised on a definition based on the projectile or projectile core being “constructed entirely (excluding the presence of traces of other substances) from one or a combination of tungsten alloys, steel, iron, brass, bronze, beryllium copper, or depleted uranium.” Certain ammunition was expressly excluded from the ban, including lead-free shot pellets and any projectile “which the Attorney General finds is primarily intended to be used for sporting purposes.” Later, the law was amended to add a second category: full jacketed projectiles larger than .22 caliber “designed and intended for use in a handgun” and whose jacket has a weight of more than 25 percent of the total weight.

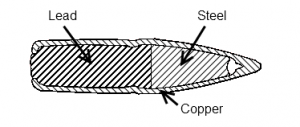

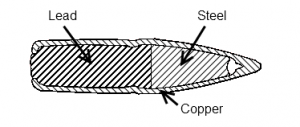

M855 “ball” ammo (and its NATO counterpart, designated SS109), sometimes called “green tip,” uses a copper-jacketed projectile with a core made in part from steel and part from lead. Since its core is not made “entirely” from steel and its jacket is less than 25% of the total weight, it does not fall within the scope of either definition of “armor piercing” ammo in the law. Nevertheless, as soon as the law was passed in 1986, ATF “granted” an unnecessary “sporting purposes” exemption for M855 ammo. In the “Framework” memo, ATF (erroneously) says “AR-type handguns were not commercially available when the armor piercing ammunition exemption was granted in 1986.” If that were true, then no exemption would have been necessary. The statute only applies to handgun ammo. Now, citing the proliferation of AR-platform handguns and glossing over the fact that its projectile core is not made “entirely” of steel, ATF singled out M855 as a specific example of ammo that would fail the criteria of its new “framework” and is withdrawing its prior “exemption.”

M855 “ball” ammo (and its NATO counterpart, designated SS109), sometimes called “green tip,” uses a copper-jacketed projectile with a core made in part from steel and part from lead. Since its core is not made “entirely” from steel and its jacket is less than 25% of the total weight, it does not fall within the scope of either definition of “armor piercing” ammo in the law. Nevertheless, as soon as the law was passed in 1986, ATF “granted” an unnecessary “sporting purposes” exemption for M855 ammo. In the “Framework” memo, ATF (erroneously) says “AR-type handguns were not commercially available when the armor piercing ammunition exemption was granted in 1986.” If that were true, then no exemption would have been necessary. The statute only applies to handgun ammo. Now, citing the proliferation of AR-platform handguns and glossing over the fact that its projectile core is not made “entirely” of steel, ATF singled out M855 as a specific example of ammo that would fail the criteria of its new “framework” and is withdrawing its prior “exemption.”

ATF is blatantly misreading the language of the federal law. The statute says:

. . . a projectile or projectile core being which may be used in a handgun and which is constructed entirely (excluding the presence of traces of other substances) from one or a combination of tungsten alloys, steel, iron, brass, bronze, beryllium copper, or depleted uranium. (Emphasis added)

Although not explained in the memo, ATF issued a “Special Advisory” dated February 27, 2015, revealing their distortion of the law:

It is important to note that the limitation on “armor piercing ammunition” in the GCA does not apply to projectiles manufactured exclusively from non-restricted materials such as copper and lead; it only applies to projectiles that include the specifically restricted materials, and can be used in a handgun.

See the difference? This is a perversion of the clear language of the law and cannot be tolerated.

What To Do?

This “framework” has been a couple of years in the making, but both the political left and right recognize it as an implementation of the President’s promise to the anti-gun lobby to use every administrative means possible to make up for their legislative failures. For a very insightful article (with only a few factual errors), see this Huffington Post blog. So, while the action taken by ATF isn’t a “ban of all AR15 ammo,” it does require a response. The question is: How do we respond effectively?

Two ways: 1) Send your comments to ATF and 2) write to your Senators and Representatives asking them to sign on to Congressional letters to ATF and to support proposed legislation that would curb ATF’s abuses in this area.

When ATF published its proposed “framework,” it invited public comments for 30 days (ending March 16, 2015). As a starting point, ATF skirted the official procedure for creating regulations that implement federal laws. (See instructions for submitting comments on page 17 of the ATF memo.)

Substantive rules of this kind are supposed to have a 90-day comment period and other steps before going into effect. Here, ATF characterized their rule change as a “framework” by which they will consider requests for exemptions for ammo that otherwise would be prohibited under the “primarily intended to be used for sporting purposes” exception and published it simply as a “notice” to the industry.

Make no mistake, ATF doesn’t care how you “feel” about their latest action, and rants about how everything they do is unconstitutional and evil will be ignored and discarded as off-topic. The only comments with any potential to influence ATF are those explaining why the proposed action exceeds or violates the agency’s statutory authority, internal conflicts or inconsistencies in what is being proposed, and unintended consequences they have overlooked. Feel free to borrow liberally from my example letter. This option is worth your time, but is unlikely to be effective alone.

Your elected officials should care how you feel — after all, they want your vote to be re-elected. But, more importantly, tell them what you think and what know about this subject (ATF’s misrepresentations in the Proposed Framework and skirting proper rulemaking procedure). Then ask them to do something specific.

Congress can apply pressure in various ways to curtail rogue agencies. The topic has picked up some inertia in Washington and even been noticed by the main-stream media outlets. A group of more than 250 (so far) Members of the U.S. House of Representatives have signed this letter to ATF Director B. Todd Jones. A similar letter is being circulated in the Senate by Chuck Grassley. Specifically ask your Senators and Representative to sign these letters. If the House or Senate Judiciary Committees schedule hearing on this topic, it may be enough to put the brakes on ATF’s plans.

Congress also has the power to change the law so it won’t be misinterpreted, although it’s hard to think of clearer language than “a projectile or projectile core . . . constructed entirely” from a specific list of materials. Articles about proposed bills being drafted can be found here and here. Specifically ask your Senators and Representative to support these efforts. When a bill is officially introduced, write again asking for support of the bill by name or number.

You can find contact information for your Senators here and your Representative here. Below is a template you can use if you wish. Please write!

Dear ______,

I am writing to you about concerns I have with the recently proposed ATF Framework for Determining Whether Certain Projectiles are “Primarily Intended for Sporting Purposes” Within the Meaning of 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(17). The Proposed Framework relies on several erroneous assumptions of fact and law, which render the entire underlying proposed framework untenable.

First, it is in direct conflict with the express language of the law. The ammunition known as M855 does not have a core “constructed entirely of . . . steel.” ATF is misinterpreting the law to allow only bullets “manufactured exclusively from non-restricted materials.” This turns the statute on its head and this kind of regulatory abuse cannot be allowed to continue. ATF’s “Framework” needlessly removes from commerce one of the most common types of ammunition used in the most common type of rifle in America today. There is no evidence whatsoever that M855 ammunition has posed a particular threat to the lives of law enforcement personnel in the last 20 years.

Second, it is an attempt by ATF to skirt the proper rulemaking process under the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. 533). ATF is proposing a significant and substantive regulatory change whose flaws would be exposed when subjected to the public scrutiny of a 90-day comment period.

I ask that you sign the letter to ATF Director B. Todd Jones being circulated among members of the [Senate/House] opposing the agency’s action. I understand that bills are being drafted and will be introduced soon to curtail ATF’s authority in interpreting the law banning armor piercing handgun ammunition. Please cosponsor or support such a bill when it is introduced.

Thank you,

************

That was the end of Glenn’s article and this is me again. There’s an important update!

First: ATF is definitely not playing fair, and is breaking its own rules. Yesterday, Katie Pavlich reported that ATF’s new regulation booklet that came out in January — which comes out every ten years and takes months to alter — had already banned the ammunition in question. In other words, the 30-day comment period which began in mid-February and ends March 16 was just for show, all along.

Then, this morning, the ATF issued a “Notice of Publishing Error.” Translation: oops, we got caught. Pay no attention to the man behind that curtain.

Contact your politicians. They need to hear from us.