Starting almost three years ago now, I lost 70 pounds over the course of a single year. I did this by simply exercising regularly, not by “going on a diet” but just by changing my activity levels.[ref] I did find that regular exercise changed my appetite, reducing it significantly and giving me a distaste for overly-sweet foods and foods high in processed carbs. But in the beginning that was a side effect, not a conscious effort.[/ref] My idealized goal was to exercise at least 30 minutes every single day, and my achieved average worked out to be a little more than 30 minutes of exercise five days a week. Yay, Team Me!

When I lost that weight, according to the NIH, I became merely “overweight” instead of “obese.” Also according to the NIH, if I lose another 40 pounds (which would put me at a weight I haven’t touched since I was 11 years old and four inches shorter than I am now), my weight would then become “normal” … the heavy end of normal.

Well, rats. So much for Team Me.

What does this have to do with the usual topic of this blog, firearms and self-defense? I’ll tell you: Right now, there’s a current in the training industry that says you can’t be a good firearms instructor unless you happen to be (wait for it) in peak physical condition.

The thinking is that you cannot possibly be serious about self defense if you don’t look the part of a warrior. Unless you are fit enough to lead a team of Special Forces, you can’t be fit enough to lead ordinary people toward knowing how to use their firearms effectively in self defense. You can’t know anything about how to protect yourself from violent crime unless you know how to protect yourself from too many cupcakes.

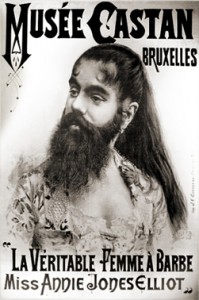

And don’t even get me started on the beard thing.

Of course, on a personal level this offends me. Despite that big weight loss, I’m still “overweight,” remember? To be honest, even though I will continue to eat consciously and exercise regularly for the rest of my life, there really isn’t much chance I’ll ever get down to allegedly-normal weight. It won’t happen because my skeletal frame really is not inclined that direction.[ref]Yup. I just used “I’m big-boned” as one reason for being the weight I am. Haters can bite me.[/ref]

Still, given that I’ve spent the past few years being relentlessly faithful with a daily exercise routine, it’s safe to say that I obviously I agree that most of us are better off when we’re in better shape. Quite apart from the long term health benefits, when you’re less hefty it’s easier to find cute clothes that fit, the airline seats feel less cramped, and you’ve got a better chance of keeping up with your kids as they ricochet around the playground.

So there’s that. But still…

What’s your take? Does someone have to be in peak physical shape in order to teach other people how to effectively use firearms for self-defense?