“Watch your front sight.”

If I had a dime for every time I’ve said that line or heard it said, I’d probably be able to buy a Starbucks Coffee. I don’t mean a cup of joe, not even a Grandad or Venetian or Giganta or whatever they call the one that holds so much caffeine you shake for two days after you drink it. I mean the entire franchise operation, lock, stock, and barrel full of Pumpkin Spice Latte.

Okay, that may be a slight exaggeration there. But only a slight one. After all, I’ve been taking classes or teaching them for more than 14 years now. On most ranges, “Watch the front sight!” gets said nearly as often as, “Shooter ready?” That’s a lot of Starbucks under the bridge.

Still, for all the times I’ve heard a range officer tell someone to watch their front sight, I have rarely heard anyone explain why we’re keeping an eye that sight, or what’s supposed to happen when we do. Are we afraid that itsy-bitsy gizmo is going to pack up and move to Tahiti, and leave us at home? Will it suddenly start dancing the macarena while wearing a tiny little rhinestone necklace? Or what? What are we watching it for, anyway?

Here’s the skinny.

Starting with the basics, the front sight is the bump on the muzzle end of the barrel. The front sight usually (not always) has a splash or dot of paint on it to make it easier to see. Sometimes the whole thing is made of something bright, like a tritium tube, designed to force your eye to pay attention to it.

Watch this space.

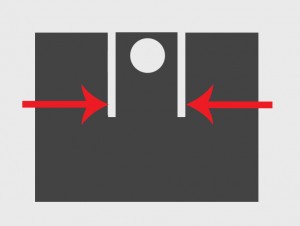

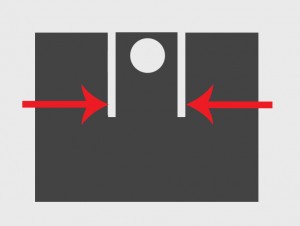

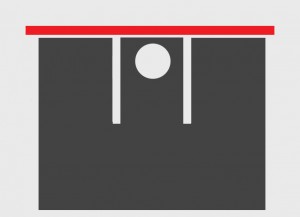

The rear sight is the bump at the end of the gun closest the shooter. The rear sight is usually (not always) notched, split, or otherwise bifurcated in some way. On most handguns, you’re supposed to visually place your front sight into that rear sight notch. Make sure it’s in the center of the notch by seeing equal amounts of light on either side of the front sight, then line up the whole shebang with the exact center of the spot you want to hit.

There should be an equal amount of light on both sides of the front sight when it’s centered in the rear sight notch.

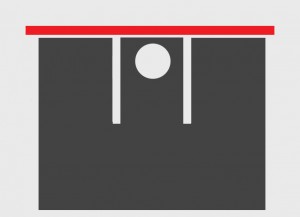

The top of the front sight should (in most cases!) line up evenly with the top of the rear sight.

In other words, the purpose of the sights is to help you hold the muzzle of your gun in a straight line with the target, like so:

Picture definitely not to scale.

Now here’s where the rubber meets the road. Or at least, where the optic nerve hits reality. Because we can’t just line the sights up once and for all and then let our concentration drift away to think about other things while we shoot. Nope! Instead, we have to continuously keep realigning the sights while we press the trigger. It’s an active process, not a passive one. And it keeps happening during the entire time we’re shooting. We can’t just do it once for all time. Or even once every two seconds.

Why not?

Well, because you’re not a robot. You’re a living, breathing, moving human being. No matter how carefully you try to stay still, your sights will always be in constant motion whenever you aim a hand-held firearm. Every tiny little movement you make will be transferred to your handgun. Even when you try to hold the gun perfectly still, you’ll still move a little bit. Your muscles will tremble just a little as they lift the weight of the gun. Your nerves will constantly signal your muscles to make tiny little adjustments in hand or finger pressure. Your balance will shift a little. Your breath will go in and out, blood go round and round – and movement of your body translates into movement of the gun. Every time your body moves even a tiny amount, your sights will move relative to the target, and the front and rear sight will also move relative to each other. You are a perpetual motion machine (though, sadly, not the type that’s worth a squintillion dollars to discover).

All of that constant, unavoidable body motion means we can’t just line the sights up once with a glance and then let fly with the trigger, KA-BLOWEE! If we do that, our shots hit unpredictably, sometimes in the right place and sometimes … somewhere else.

Nor can we just yank the trigger back, superfast, just exactly at the very instant we think the sights are finally, truly, really aligned. We can’t do that because a sudden jerk of the trigger almost always throws the shots off target (usually low and to the left for a right handed shooter, though there are other patterns). It doesn’t work because no one actually moves faster than their own optic nerve. What you saw .003 seconds ago isn’t the world as it actually is right now, nor can you somehow get your muscles moving quickly enough to time travel and bridge that gap.

So if sudden explosive trigger-slapping isn’t the answer, what is? Smooth, even pressure on the trigger, and continuous realigment of the sights.

To hit the target accurately and reliably, you must keep realigning the sights during the entire shooting process – from the time your finger touches the trigger, while you press the trigger smoothly, while you bring the trigger back evenly to its break point. Even while recoil happens, you hold the trigger to the rear as you realign the sights. Keep realigning your sights continuously until you decide to quit shooting, then lift your finger and place it alongside the frame before you bring the gun off target.

In other words, as long as your finger is touching the trigger, you must constantly check and recheck the sights, adjust and readjust the aiming details, so you can keep the muzzle lined up with where you want to hit. As long as you keep lining the sights up while you press the trigger, the bullet will hit the center of your target no matter when it leaves the barrel.

That’s why “watch the front sight!” is such common, and such uncommonly good, advice.