An excerpt from a recent newsletter by John Farnam (by the way, if you are not a regular reader of his, you are missing out — and his name should be near the top of your bucket list for firearms training, too).

Here he is talking about molded-plastic replica guns, sometimes called ‘dummy guns.’ They are solid pieces of plastic with no moving parts whatsoever.

The sentence in bold highlights something I want to talk about today, but it’s worth reading the whole thing — more than once. And thinking about it too.

***

Quote from Farnam’s Quips, 1/23/18:

“I find [Ring’s Blue Guns] useful in showing students, in a classroom, how to grip guns, how to avoid pointing guns in unsafe directions, and general correct gun-handling. Because they’re inert, we can graphically demonstrate to students the ‘wrong way’ of doing things. For that, I find them a wonderfully useful training-aid….

“But, there are those who decree that blue guns be strictly handled exactly the same as functional guns! They insist that blue guns never be ‘pointed’ in ‘unsafe directions.’ They thus don’t allow blue guns in the classroom – but they do allow functional guns.

“This is insanity!

“What are blue guns for?

“Whether or not you like blue guns, functional guns, regardless of their supposed ‘condition,’ should not be handled in the classroom in any event!

” ‘Condition-based training’ with functional guns is inherently defective. When you have ‘safe guns’ and ‘dangerous guns’ in your life, it is just a matter of time before they get mixed-in with each other!

“Functional guns are dangerous, all the time, and we handle them as such. That is why we run ‘hot’ ranges.

“Blue guns are not functional. They are not ‘guns’ at all. It is thus safe, and appropriate, to handle them in the classroom for instructional purposes!”

***

A few thoughts of my own, building on Farnam’s excellent points.

Dummy guns are — by definition — completely inert. They cannot hold a round of ammunition, and could never launch a bullet even if they could. They are utterly harmless in their physical being. Even getting bopped on the head with one isn’t the end of the world, and is relatively painless.[ref]This is very much unlike the aluminum castings used as dummy guns for role play in an earlier era… don’t ask me how I know this. Trust me: I know this.[/ref]

This does not mean dummy guns are “safe” in some ultimate sense. It only means that there is little or no physical danger in handling them.

Dummy guns are extremely dangerous in one particular way: they are shaped like a gun, but they can never launch a bullet. This creates a constant and unrelenting pressure to handle them without thought or care. But habits built with dummy guns carry over into habits used around real guns.

That’s why we use them: because they help us build longstanding habits.

It is entirely up to us whether the habits we build with our dummy guns are good habits, or bad ones. And bad habits are dangerous. As I’ve often said, injuries from loaded guns usually arise from longstanding bad habits with unloaded ones. This goes just as strongly for habits built with inert dummy guns.

Good uses for dummy guns

It is perfectly okay — not just acceptable, but downright admirable — to use dummy guns to unlearn bad habits and learn the correct ones. And yes, that does mean that sometimes we will do things with a dummy gun that would be bad and dangerous to do with a functional gun. That’s why the dummy gun exists, after all.

Dummy guns work very well in the classroom when an instructor uses one to demonstrate the “wrong” way to do a thing, and then show students how to correct that error.

They work well for role play and force-on-force exercises. This includes the type of role play where one student (playing the good guy) points a gun at another student (playing the role of attacker). It also includes settings where people practice ways to physically hold onto the gun while entangled with an aggressive attacker.

More than that, it is truly wonderful to use a dummy gun at home for various things including holster practice. I honestly believe that every person who owns a firearm for concealed carry should also own a dummy gun for regular work with the holster. Dummy guns are especially useful when trying on a new holster or exploring a new type of carry method.

Protecting good habits while demonstrating bad ones

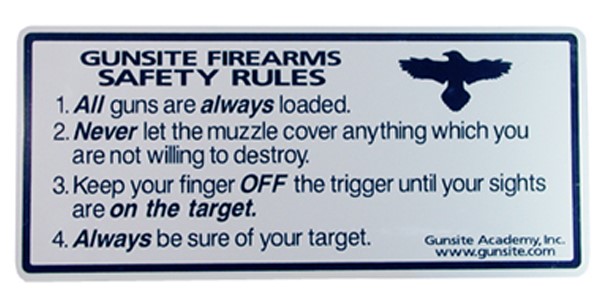

Because dummy guns build habits, we should work hard to protect our own good gunhandling habits whenever we use one. We also want to model good gunhandling habits for others. While this is especially true for instructors, it’s also true for anyone who wants their loved ones to handle firearms safely and well. So whenever we handle dummy guns, we do it with deliberate and conscious awareness of the habits we are building for ourselves, and also of the habits we are showing to others.

But how can we do that, if one of the purposes of dummy guns is to allow us to safely show others bad habits to avoid?

Here’s one way. When I teach classes, I have a schtick where I use a dummy gun to show students all of my … ahem… “favorite” … ways people point guns at themselves on the range without realizing it. During this segment of the class, I do the following with a dummy gun:

- Pretend I’ve just finished shooting the target, and am relieved — so I relax, let the gun drop suddenly toward the ground, pointing it at my knees and feet while it dangles thoughtlessly alongside my leg.

- Pretend I am irritated with my own shooting, and jerk the gun angrily down toward my own feet.

- Pretend I am putting the gun into the holster, and reach over to steady the holster with my left hand while holding the gun with my right, thus passing the muzzle of the gun over the top of my left hand before it goes into the holster.

- Pretend I can’t find the holster mouth, so I’m pointing the gun’s muzzle directly into my body’s core as I use the muzzle to blindly seek for the holster mouth.

- Pretend I suddenly realize I’ve forgotten my hearing protection, so I slap my hands to my ears … with the gun still in hand.

- Pretend I am having a hard time racking the slide, so I point the muzzle into my own abdomen while I try to get leverage to get the slide moving.

Pretty soon, the students start making suggestions of their own about bad gunhandling they have personally seen. And they get the point about how easy it is to do, when we aren’t paying attention. Done properly with lots of class interaction, this can be a wonderful teaching aid that always gets everyone laughing and thinking about how they handle guns. But even with all this misbehavior, there’s one very important thing about what I am doing with the dummy gun: every wrong thing they see me do, they see me do deliberately. It is within the context of “things not to do” and we are all very clear on that. And I do each one separately and consciously, with full awareness of what I am doing with the gun-shaped object in my hand. This helps me maintain my own good habits. It also helps students avoid learning bad gunhandling habits, because I have drawn their attention to the fact that these are bad habits.

My ‘bad’ gunhandling with a dummy gun is never unintentional. I want the people around me to be able to tell that I am making a deliberate error in order to show them how to correct that error. Each mistake is made on purpose and for a purpose.

When I am done showing people what that wrong thing is and how to correct it, I get the dummy gun out of my hand by putting it on a desk or in a holster or on the ground. Or I go back to holding it carefully with the muzzle in a known and controlled orientation, consciously keeping my hands still as I talk so that I am again modeling correct behavior until it is time to deliberately model bad behavior.

Thoughtless habits to avoid

Many of us tend to wave our hands around a bit when we talk. That’s natural. So when you keep a dummy gun in your house for practice, don’t get in the habit of waving it around while having a conversation with your spouse. If you have one in the classroom, don’t keep it in your hand while you’re lecturing, especially not if you’re in the habit of talking with your hands.

Talking with your hands is fine, but thoughtlessly waving a gun-shaped object around is Not Okay — that’s a bad habit and it’s poor modeling for others.

Don’t use the muzzle of the dummy gun to scratch an itch, or gesture toward something across the room, or just to fiddle with while you’re watching television. You don’t want to get in the habit of not really noticing the thing in your hand that’s shaped like a gun.

Whenever you handle your dummy gun, make a habit of picking it up properly with a solid grip and do keep track of the muzzle direction as you do it. If you’re holding onto it as you move around the room, remain aware of what’s in front of the muzzle as you move.

If circumstances make it inconvenient to keep the dummy gun in hand with a proper grip as you maintain muzzle awareness, then get it out of your hand or at least change things around so it does not feel like a gun in your hand anymore. For example, you might plunk it into a bag, or pile it onto a stack of other non-gun things to carry — and then you can relax without concern. The goal is to maintain your own good habits for handling firearms, not to get prissy and persnickety about a simple piece of plastic.

Never thoughtlessly park a finger on the trigger of a dummy gun for no other reason than “because it’s there.” Guard your good habits.

Role play

Pretend guns — dummy guns — are made for playing pretend. And that’s what role play really is. Never use a real gun for role play. Real bullets can get into real guns, and then the gun can really fire and a real person gets hurt or killed. For real.

When you must point a gun-shaped object at someone, that someone should always be an appropriate target for such an action, within the conversation you are having with them.

For example, an instructor might point a dummy gun at a student who is role-playing an attacker, and that’s good. But it’s not good to point a gun-shaped object at that same student just to indicate that it’s their turn to speak during a class discussion. That doesn’t fit the conversation.

Because imagination and visualization exercises require active participation, always make sure other people (students, friends, family members) expect and consent to this type of role play before pointing a gun-shaped object in their direction.

Real or Pretend?

Some instructors like to “designate” a safe direction for classroom use. Used in this sense, “designate” is a jargon-ish word that means, “This direction isn’t really safe but we’re going to pretend it is.”

It is okay to pretend that’s a safe direction as long as we are using a pretend firearm, which is what a dummy gun really is.

But the moment the gun becomes real, the safe direction had better become just as real.